We recognised early on at Aurora that victims and survivors both working in and linked to the armed forces needed bespoke specialist provision and as such we set out in 2017 to establish a pilot project to address the gaps in service provision.

We were lucky to receive funding from the British Legion for the pilot project and from 2018 gained funding from the Armed Forces Covenant Trust to provide a service to address the needs of victims of domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking for the British Army, The Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force.

We have learnt a great deal over the last four years and our partnership with colleagues in the armed forces has grown exponentially. But most importantly for us we feel so privileged to have supported the many victims and survivors who came forward very bravely to use our service. We thank them for their trust in us and will work hard to ensure this much needed service continues.

You can see a copy of the full report in pdf format here:

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this report, do not hesitate to get in touch.

Want to help? You can help Aurora raise vital funds during the COVID19 pandemic:

‘INDEPENDENT, BUT ALONGSIDE’

– An Evaluation of the Multi Specialist Armed Forces Advocate Project

Dr Jacki Tapley

November 2020

CONTENTS

- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary of Terms

- Introduction

- Aims of the evaluation study

- Background to the Armed Forces Project

- Findings

- Barriers to disclosing and identifying domestic violence and abuse

- Individual barriers

- Organisational barriers

- Raising awareness of DASVS – training and resources

- The dual role of the multi specialist Armed Forces Advocate

- The value and impact of partnership working

- Demand and capacity

- Future challenges

- Conclusion

- References

- Appendices

- How can I help?

Executive Summary

Changes in attitudes towards domestic violence and abuse

The last three decades have witnessed a significant shift in public and political attitudes towards domestic violence and abuse (DVA). Albeit gradual and at times frustratingly slow, the significance is that DVA is now widely recognised as a legitimate public concern, rather than solely as a private matter to be tolerated and condoned. The serious harm suffered not only by the victims and their children, but wider society too, has now been recognised and reflected in the ascendance of DVA on the political agenda, resulting in a substantial number of policies and reforms since the 1990s (Strickland and Allen, 2017). Whilst still awaiting its final passage through the House of Lords, the Domestic Abuse Bill 2019-21 will for the first time, create a statutory definition of domestic abuse, emphasising that domestic abuse is not just physical violence, but can also be emotional, coercive or controlling, and economic abuse (Home Office, 2020).

Addressing abusive and inappropriate behaviour within Armed Forces communities

In 2018, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) published its first DVA Strategy, No Defence for Abuse, outlining its commitment to addressing abusive and inappropriate behaviour within its Armed Forces communities. Subsequent reports have found evidence of a need for cultural change (MOD 2019; 2020a), acknowledging the factors related to military service that may increase the likelihood of DVA, the barriers that may impede the identification and disclosure of abusive behaviour, and the limitations of the Armed Forces to provide effective and independent support services for victims and survivors. In recognition of the high levels of mistrust found in the chain of command, the MOD strategy demonstrates a willingness to engage with external organisations, to increase collaborative working with specialist partner agencies and to share and learn from best practice (MOD, 2018).

Aurora and the Armed Forces

This report presents the findings of an evaluative study, examining the outcomes of a collaborative partnership between a local charity based in Hampshire and the Armed Forces. Aurora New Dawn (Aurora) is now in the final year of a three-year Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust grant to develop an Armed Forces Advocate project. The key aims of the project are to provide military personnel and their families’ access to specialist independent support regarding domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking (DASVS) and to provide specialist training to relevant Armed Forces personnel, particularly those working in policing and welfare related services, to raise awareness and improve their understanding of DASVS. A significant feature of this project is the ability of Aurora to offer a multi specialist advocacy service covering domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking, rather than providing single service advocacy. A particular aim is for Aurora to utilise their specialist knowledge and experience of providing advocacy to survivors across all three areas to identify the essential elements required to deliver a bespoke service for Armed Forces personnel.

The Armed Forces Advocate

Adopting a small-scale qualitative methodology, this evaluative study has examined the role of the specialist Armed Forces Advocate (AFA) and their contribution to the military response to and management of DASVS. In particular, the research has explored how the knowledge and expertise gained from delivering specialist advocacy services improves the outcomes for victims and survivors, and the wider impact upon Armed Forces responses to DASVS and victim care. The study involved semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders, an observation of and feedback from Stalking training workshops, referral data and feedback from victims and survivors who received support from the AFA. This report acknowledges the problematic use of terminology when referring to people who have experienced abuse and uses the terms ‘victim’ and ‘survivor’ interchangeably throughout the report, drawing upon the phrases and terms most used by the participants.

A number of superordinate themes and subthemes emerged from the qualitative data, highlighting the unique characteristics of military life and the benefits for military personnel and their families. However, it also revealed the institutional and individual barriers that exist when individuals experience inappropriate and abusive behaviour, whether by an intimate partner, friend, associate or stranger. The barriers can occur at all stages, from decisions regarding the initial disclosure, subsequent responses by those informed, accessibility to support, and information about the criminal justice process.

The success of the Armed Forces Advocate project

The AFA project demonstrates how such partnerships can work successfully to improve the outcomes for military personnel and their families, when there is greater awareness of DASVS and improved responses delivered in collaboration with independent specialist services. By recognising both the individual and organisational barriers that exist, the AFA Project has developed collaborative partnerships with key stakeholders to raise awareness of DASVS, provide and deliver specialist training to over 500 military personnel across the Armed Forces, and delivered specialist support to over 130 victims and their children.

By listening to the views of key stakeholders and, most importantly, the victims’ perspectives through feedback received, this research has identified the essential criteria required to deliver a bespoke domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking (DASVS) specialist service to military personnel and their families. In particular, the service needs to:

- be independent from the military chain of command

- have an insight and good understanding of the military context

- have specialist knowledge of domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking

- be responsive, to listen and be non-judgemental

- work with, respect and acknowledge decisions made by the survivor

- be accessible via different methods of communication

- provide emotional advice and practical information

- have a good knowledge of the criminal justice system and victim-centred processes

- be there in the longer term for ongoing support, advice and reassurance

- to provide a link between the survivor and the military support services to ensure consistency and continuity of support

- to develop and maintain collaborative partnerships with all military services

Feedback received from a range of sources has provided evidence of the professional services provided by Aurora through the AFA Project and the improved outcomes for victims, survivors and military personnel. The collaborative partnership working and the extensive training provided has contributed to a greater awareness and understanding of DASVS, an increased confidence in responding to DASVS and improvements in victim care.

Acknowledgements

I would like to give a special thanks to everyone who so generously gave up their time to contribute to this report. Despite having an understanding of DASVS, my knowledge of military life, the culture and the processes was extremely limited and this research has provided a fascinating insight to the complexities of life in the Armed Forces. I hope that the findings of this report, and the voices of all those who contributed, will assist in moving forward policy and professional practice, to create a culture where everyone feels able to speak out, be heard and receive specialist support.

Glossary of Terms

Introduction

The change in attitudes towards domestic violence and abuse

The last three decades have witnessed a significant shift in public and political attitudes towards domestic violence and abuse (DVA). Albeit gradual and at times frustratingly slow, the significance is that DVA is now widely recognised as a legitimate public concern, rather than solely as a private matter to be tolerated and condoned. The serious harm suffered not only by the victims and their children, but wider society too, has now been recognised and reflected in the ascendance of DVA on the political agenda, resulting in a substantial number of policies and reforms since the 1990s (Strickland and Allen, 2017). Whilst still awaiting its final passage through the House of Lords, the Domestic Abuse Bill 2019-21 will for the first time, create a statutory definition of domestic abuse, emphasising that domestic abuse is not just physical violence, but can also be emotional, coercive or controlling, and economic abuse (Home Office, 2020).

Our greater awareness of the nature and extent of domestic abuse is indebted to the tireless campaigning of grass roots feminist activists since the late 1800s and the development of third sector specialist support services since the 1970s (Harne and Radford, 2008; Tapley, 2010; Tapley and Jackson, 2019). Challenges to the patriarchal values and structures that have dominated powerful state institutions has resulted in significant cultural changes in political, social, criminal justice and legal professions and has more recently permeated the military in the UK. Whilst possessing unique characteristics, the Armed Forces are a microcosm of wider society and have not been immune to the increasing awareness of domestic abuse and sexual violence within its own ranks. As a department with ministerial responsibility, the UK Ministry of Defence is required to follow national guidelines and legislation and as such, has engaged with the wider Government strategy to end violence against women and girls (VAWG) in all its forms, first introduced in 2010 (Home Office, 2016).

No Defence for Abuse

In 2018, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) published its first DVA Strategy, No Defence for Abuse, outlining its commitment to addressing abusive and inappropriate behaviour within its Armed Forces communities. It found evidence of a need for cultural change in its own reports and surveys, including a review by Air Chief Marshal Wigston (MOD, 2019), commissioned by the MOD to look into inappropriate behaviour in the Armed Forces. The report made 36 recommendations focusing on improving the complaints process and preventing inappropriate behaviour in the first place. The aim of a further report, commissioned by the then Defence Secretary, Gavin Williamson MP, was to provide an independent review of the diverse needs of Service families to increase awareness of the challenges they face and to ensure they are not disadvantaged by the impact of military life (Living in our Shoes, MOD, 2020a) . These principles are enshrined in the Armed Forces Covenant, introduced in 2012 under the provisions of the Armed Forces Act 2011.

The MOD Strategy (2018) acknowledges the factors related to military service that may increase the likelihood of DVA, the barriers that may impede the identification and disclosure of abuse behaviour, and the limitations of the Armed Forces to provide effective and independent support services for victims and survivors. Under the three key pillars of Prevention, Intervention and Partnering, the strategy identifies a number of key actions – awareness raising, specialist training, and the development of partnerships with external organisations. The longer-term ambition is to achieve a cultural shift across defence, such that a greater awareness of and response to DVA is considered a core business issue and for DVA to be identified early and tackled proactively through peer and management support. One key area raised as an action point in order to achieve this ambition is the need to address the reluctance of military personnel and family members to disclose DVA. It is now recognised that a number of barriers exist, in addition to those that contribute to the underreporting of DVA in wider society more generally (Williamson and Price, 2009). These additional barriers relate to the uniqueness of military life and include the emotional and material losses associated with, what could potentially result in the loss of a whole way of life: the impact on status, reputation, careers, housing and children’s education. This reluctance to disclose is compounded further by a lack of confidence in the system and a fear of the consequences of doing so:

‘Military culture and a rigid hierarchy inhibits bystander intervention and the ability of lower ranks to challenge the behaviour of their seniors. Such fears include the impact on their career prospects; being perceived as a trouble-maker; the issue being placed on their career record…. Not being believed, their concern not being taken seriously; and the chain of command at every level lacking the time to do anything with the issue.’

(MOD, 2019: 13)

In an effort to acknowledge and address the high levels of mistrust, the MOD strategy demonstrates a willingness to engage with external organisations and to increase collaborative working with specialist partner agencies in order to help them to understand Service life, develop suitably tailored (bespoke) services, and to share and learn from best practice (MOD, 2018).

Independent Academic studies into Domestic Violence and Abuse within the Armed Forces

In addition to the reports commissioned by the MOD, the uniqueness of military life and the prevalence of DVA within the Armed Forces has become the focus of a number of independent academic studies. A study by Williamson et al (2019) identified some of the critical factors that help to define a specialist DVA service within a military context. These include a collaboration between DVA civilian and military service providers, and an awareness and understanding of the wider military context. A further study by Sparrow et al (2020: 1) critically explored the perspectives and experiences of Armed Forces healthcare and welfare professionals in identifying and responding to DVA among the UK military population, including serving personnel, veterans and their families. Three key themes emerged from their findings:

- Patterns of DVA observed by health and welfare workers – perceived gender differences in DVA experiences and the role of mental health and alcohol abuse. Whilst not perceived to be the causes of DVA, participants identified these as contributing factors to DVA in the military.

- Barriers to the identification of and response to DVA – attitudinal/knowledge-based barriers and practical barriers. In particular, the persistence of a ‘macho culture’, a reluctance to be perceived as weak and the stigma associated with DVA, thereby deterring disclosure and limiting help seeking behaviour.

- Resource issues – training needs and access to services – in particular, participants emphasised a lack of specialist training with some feeling ill-equipped to manage cases of psychological abuse and coercive control. Consequently, levels of confidence in responding to DVA varied widely.

Partnerships with DVA advocacy/specialists

In particular, the Armed Forces healthcare and welfare professionals were aware of high levels of concern regarding a lack of confidentiality within the welfare services, and of service personnel fearing the consequences of reporting DVA on their careers or that of their partners. The study found that the majority of participants cited the importance of integrated working between civilian and military services to improve the management of DVA and the associated risks, and a need to increase access to support services to provide effective care to both victims and perpetrators (Sparrow, et al. 2020:12). The study identified that:

‘There is a particular training need among healthcare and first-line welfare staff, who are largely relied upon to identify cases in the military. Employing DVA advocates within military and civilian healthcare settings may be used in improving DVA awareness, management and access to specialist support.’

Sparrow et al (2020) referred to examples of partnerships with DVA advocacy/specialist services in healthcare settings and the value of providing a clear referral pathway for GPs to refer into a DVA advocate/specialist service. One such model is the IRIS Project (Feder et al, 2011).

Of particular note, the authors observe the current lack of research on effective practices in the identification and response to DVA in the UK military and highlight the urgent need for further research, concluding:

‘Evaluation of a similar intervention in military settings would be very helpful in establishing whether there may be a beneficial role for DVA advocates within military healthcare settings to improve identification and the referral pathway to specialist support.’

(Sparrow, et al. 2020: 15)

The development of partnerships with civilian specialist support services is a key pillar of the MOD strategy and, acknowledging the lack of current research in this area, the strategy highlights a need for research to inform and support the further development of policies and practice. The focus of this report is to evaluate an Armed Forces Advocate pilot project to explore the role of a specialist advocate and the benefits this may bring to the military response to and management of DASVS. In particular, it examines whether the role of a specialist Armed Forces Advocate (AFA) improves the outcome for victims and survivors.

Aims of the evaluation study

Aurora New Dawn (Aurora) is now in the final year of a three-year Armed Forces Covenant Fund grant to deliver a specialist DASVS advocacy service. As part of the AFA Project they wanted to ensure that the learning gained from the service is centralised into an independent evaluation via academic research and commissioned Dr Jacki Tapley, University of Portsmouth, to undertake an evaluation. The effectiveness of the project is measured by how well it achieves the following outcomes, which are reported quarterly as part of the funding agreement:

Outcome 1: Military families and personal will have increased access to specialist independent support regarding domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking.

Outcome 2: Relevant armed forces personnel will receive specialist training on Stalking including Coercive Control.

Outcome 3: Transfer of the model of Hampshire multi agency Stalking Clinic. This will be put into practice in year 3 of the project with full consultation with armed forces partners. It may be more viable for the model to be a virtual one, given the transient nature of the armed forces community.

In addition to assessing the overall indicators above, the key aim and specific focus of this study is to gain an in-depth understanding of the impact of the AFA Project on the outcomes for victims and survivors. In particular, to identify the additional benefits a bespoke service that has specific knowledge and understanding of forces life, has made to the outcomes for service personnel and their families.

Methodology

Dr Jacki Tapley was commissioned by Aurora to undertake the evaluation, due to her knowledge and understanding of the work of Aurora (in her role as a Trustee) and her wider experience as an academic researcher (Principal Lecturer in Victimology at the University of Portsmouth). Dr Tapley has substantial experience of undertaking research with victims of crime and evaluative studies involving partnerships with criminal justice agencies, the third sector and government institutions. A consultation with the Board of Trustees regarding the independence of the evaluation was undertaken. It was agreed, due to the sensitivity of the research and to maintain the trust that Aurora has established with the Armed Forces, for the research to be undertaken by someone who has both knowledge of the subject area and the organisation and, as a consequence, will be trusted sufficiently by military personnel to engage with the research.

Literature on domestic abuse and the military

Given the time available and the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, a small-scale qualitative research methodology was utilised. A review of the existing literature was undertaken. Whilst there is substantial literature on domestic abuse, the development and implementation of policies, and research on victim-centred interventions in wider society, there is significantly less on domestic abuse and the military, and even fewer on the development and evaluation of partnerships between outside specialist organisations and the Armed Forces (Williamson and Price, 2009; Williamson et al 2019). It is not the remit of this study to provide a review of the wider literature, but Sparrow et al (2020) provide an informative and extensive review of the relevant literature and their research highlights the fundamental complexities when examining the military response and management of DVA in a wider context.

Interviews

To achieve the aims of the study, semi-structured interviews were held with key stakeholders from the Army and the Navy. Unfortunately, it was not possible to gain access to a representative from the RAF in the time available. Interviews were undertaken with five representatives from the Armed Forces, including both civilian and military personnel, occupying different ranks and roles in welfare, policy and leadership. Two members of Aurora staff were interviewed; the first has contributed to the project since its inception and is involved with the delivery of training; and the second is the AFA who delivers the advocacy service. An interview was also undertaken with an independent person who works with victims and survivors of DVA in their role with a statutory organisation, and has worked closely with the military regarding DVA. With the exception of one interview, all interviews were held via Zoom due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The one face-to-face interview was held observing social distancing rules. A purposive sampling strategy was utilised, as this is central to a qualitative approach when the aim is to gain an in-depth understanding of the perceptions and experiences of those involved in the project under review:

‘Random or representative sampling is not preferred because the researcher’s major concern is not to generalize the findings of the study to a broad population or universe, but to maximise discovery of the heterogeneous patterns and problems that occur in the particular context under study.’

(Erlandson, Harris, Skipper and Allen, 1993: 82)

An ethics review was undertaken. All participants were informed of the aims and the purposes of the study, participation was voluntary and informed consent was gained from those who were interviewed. The anonymity of participants is important to encourage participants to speak freely. Quotes from participants are included in the report, but they are not identified individually by service, role or rank, due to the small number of participants, and the possibility their role may only be performed by one person in their organisation. Specific cases were discussed during the course of interviews, but no names or personal details were disclosed.

In addition to the semi-structured interviews, the researcher observed an online training event focusing on Stalking. This was delivered via Zoom by a member of the Aurora team and attendees were representatives from across the three Armed Forces. Information regarding referrals was gained from the data recorded by Aurora and reported quarterly as part of the funding agreement. This data included important feedback from victims and survivors who had received information, advice and support from the AFA. It is fundamental that the voices of victims and survivors should be central to any evaluation of a service aimed at delivering support to them. Interviews with a small number of survivors had been intended, but due to the sensitivity and potential vulnerability of the survivors, and the fact that these could no longer be undertaken face to face with the necessary support provided, it was decided to postpone the gathering of further feedback from victims and survivors until it was safe to do so.

Aims and objectives

This is a small scale qualitative study, supported by data gained from a range of sources, aimed at understanding the impact and benefits of a multi specialist AF Advocate provided by an outside organisation working collaboratively with Armed Forces personnel to improve the response to and support of DASVS victims and survivors in the military. In accordance with the principles outlined in the MOD (2018) strategy and the Joint Service Publication 913 (the Tri Service Policy on domestic abuse and sexual violence), the aims of the study are to examine the ability of the Armed Forces Advocate Project to promote:

- the development of joint working and training to raise awareness of DASVS

- a shared understanding of the harms caused by abusive behaviour and to provide an effective response through the delivery of an independent multi specialist support service

- to examine the influence of this collaborative approach on professional cultures and practices in the military context

- and, most importantly, to examine the impact upon the outcomes for victims and survivors

Background to the Armed Forces Advocacy Project

Who are Aurora?

Founded in 2011, Aurora is a registered charity providing safety, support, advocacy, and empowerment to survivors of domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking. An independent local charity based in Portsmouth, Aurora offers a wide range of specialist advocacy services across Hampshire and has developed innovative practices to meet local needs. These include the introduction of the DV (Domestic Violence) Car (a partnership with Hampshire Constabulary); a Stalking Advocate working in partnership with the Hampshire and Isle of Wight (IOW) Stalking Clinic to provide a multi-agency response for victims of stalking; the IRIS programme (Identification and Referral to Improve Safety), which provides training, support and a referral programme to primary healthcare staff in Southampton; and, the provision of specialist training programmes to a range of professionals.

Aurora and the military

A number of staff at Aurora have a personal link to the military, through family members who are or have been serving personnel. However, despite operating in a county with large military communities, staff at Aurora soon became aware they were not seeing people from military families and began to ask ‘Where are the families?’ Despite their certainty of a need for DASVS support services, Aurora found it difficult to engage with the Armed Forces and believed that additional barriers made it equally difficult for military personnel and families to engage with them. Disturbed by their absence, Aurora persisted and in 2017 gained British Legion funding to undertake a pilot Armed Forces Advocacy (AFA) Project, with the aim of supporting military personnel and/or their families experiencing domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking.

The aim of the pilot was to enable Aurora to build upon their knowledge and experience of delivering specialist support to survivors, and develop this further to offer a bespoke service to Armed Forces personnel. During the first year, progress was slow with very few referrals, although there was some engagement with clients. As observed by a member of the Aurora team:

There are significant challenges of working with the military…. It’s a huge institution, historically secular, with all services provided internally. It’s not used to referring outside, it’s not their way of working. Forces life is very secular, the nature of the community, who knows, who finds out, the impact on reputation and career, lots of barriers to disclosing.’

‘It has been a steep learning curve; understanding the etiquette, the chain of command. Most important is respecting the culture, not compromising their principles, but that doesn’t mean we’re shy on challenging them. We have had to prove ourselves, but it has been a two-way process.’

As with the development of any new initiative, especially one in such a complex environment, there were a number of false starts. It took time to establish contacts with the relevant people and to develop a mutual trust. Since the first pilot began in March 2017, there have been three Armed Forces Advocates. The first Armed Forces Advocate (AFA) was appointed in March 2017 and their post ended when the British Legion funding ended.

‘The first AFA had an office at Eastern HQ. We looked at developing a strategy with Aurora, a bit of trial and error, how can we get into the service community? We’ll go into the service community. In hindsight that wasn’t a good plan – if you want people to speak to you, don’t put them [the AFA] in police HQ!’

The project gained impetus when Aurora received further funding from the Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust (previously Libor funding), which enabled Aurora to work with Armed Forces communities and families on a tri force basis. The role of the AFA was relaunched and a new AFA was appointed in April 2018. The second AFA sought to raise awareness of their role by attending community events, for example, regular coffee mornings organised by the Maternity Cell for expectant mothers. However, the perceived lack of knowledge and understanding of Armed Forces family life undermined the credibility of the AFA and this created a barrier to engaging meaningfully with the families.

Despite the slow progress in establishing the role of the AFA, the delivery of specialist training by Aurora to Armed Forces professionals across the three forces – Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, assisted significantly in raising awareness of the AFA project. In particular, it enabled Aurora to raise their profile and build a reputation within military circles.

‘The first thing I remember, is when they [Aurora] delivered some training, early on, DASH training, a day event, that’s the first time I met them. It was really informative, helped to raise my awareness of risk and what to look for.’

‘I first became engaged with Aurora quite early on, they received funding for a pilot. They were really, really engaging, really early on in that relationship. I kind of owe them a lot, they were the only professional body I could speak to in terms of developing my knowledge and understanding, just my perspective around risk management, what that means around protecting victims and safeguarding plans, we’ve always had a good relationship ever since.’

‘I found the training brilliant. They take the audience into account. Aurora really get the military… it’s more interactive… and the thing is, if someone comes up with “well, I think I’d do that..”, they will say “well you wouldn’t, because…” they explain why, give examples…’

‘What has been really important for us is training around domestic abuse. We do deliver training at our college, but it’s not accredited training. Most police forces in the UK use accredited training through SafeLives now, we’re still battling for funding for that. So we had a real gap in training, a real gap in knowledge in terms of organisational knowledge and capability and Aurora really filled that gap by offering that training.’

‘Loads of our officers have been on various training workshops with them, domestic abuse, coercive and controlling behaviour, stalking, risk management, that’s been a real big help. But, of course, their primary function is supporting victims, so all our victims of DA, sexual violence and stalking will be offered a referral to Aurora, they are our number one provider, before any other service. We really utilise them quite well.’

Establishing trust and credibility in a hierarchal institution based on meritocracy can be a daunting challenge and progress can be slow, but the appointment of a third AFA in October 2018 marked a significant turning point in the project. The significance of the third AFA was that she came from a military background, being the partner of military personnel, and she brought with her a rich experience and knowledge of military life and culture, both in the UK and abroad. Whilst acknowledging that this dual role can be challenging and ‘has to be sensitively managed,’ the insight and understanding of military life that the third AFA brought to the role assisted in gaining the trust and confidence of those around her: ‘You need to know their way of life, there are lots of barriers. You have to understand what we’re leaving… not just our marriage, we’re giving up our lives.’ Importantly, to protect individuals and ensure confidentiality, if a case involves a family known to the AFA or are associated with her partner’s regiment, the case is managed by another member of the Aurora team. The AFA highlighted the many benefits of service family life, but added a caveat: ‘So wonderful… but at the same time, so damaging.’

Findings

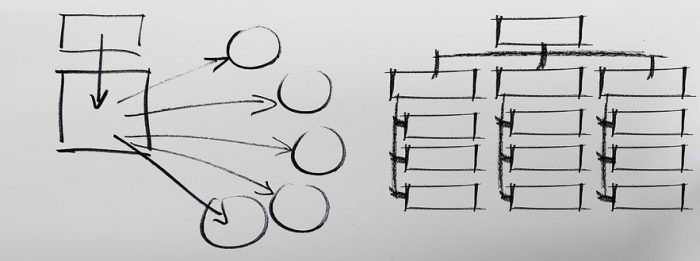

The data from the digital interviews was transcribed by the researcher and analysed using an inductive thematic analysis (Silverman, 2020: 228). A coding frame was developed based upon the topic themes used for the semi-structured interviews. A number of overarching codes were identified and then further amended and reviewed as the analysis progressed. A number of superordinate themes and subthemes emerged from the qualitative data, highlighting the unique characteristics of military life and the benefits for military personnel and their families. However, it also revealed the institutional and individual barriers that exist when individuals experience inappropriate and abusive behaviour, whether by an intimate partner, friend, associate or stranger. The barriers can occur at all stages, from decisions regarding the initial disclosure, subsequent responses by those informed, accessibility to support, and information about the criminal justice process. From the analysis of the qualitative data, three superordinate themes emerged:

- Barriers to disclosing and identifying domestic abuse, sexual violence and stalking (DASVS) at both an individual and institutional level.

- Raising awareness of DASVS at both an individual and institutional level. This theme examines the role of leadership, specialist training and access to support services.

- The dual role of the multi specialist AFA – this theme examines the dual role of the AFA. Their value as an independent advocate at an individual level and their role as a partner and collaborator at an institutional level. This dual role enables the AFA to gain trust, confidence and credibility with both victims/survivors and military/civilian personnel. Most importantly, the role of the AFA acts as a go-between, a crucial link between the individual and the institution, their independence affording them the ability to question and challenge.

See Appendix A for a chart that summarises the superordinate and subthemes at both individual and institutional levels.

Barriers to disclosing and identifying DASVS

As indicated above, it is now widely acknowledged that military personnel and their families face additional barriers to disclosing DASVS. Both Civil Service and Single Service Surveys reveal shortcomings in the complaints system, with complainants citing a lack of faith that appropriate action would be taken and fears that it may adversely affect their career (MOD, 2019). This study found that these barriers operate at both an individual (micro) level and an institutional (macro) level. All participants were able to identify these barriers and demonstrate an understanding of how they may increase an individual’s reluctance to disclose. At the organisational level, where recognising the problem is just the first step to developing strategies to overcome cultural barriers, participants discussed the role of leadership, the processes in place for developing policy and the increasing willingness to develop partnerships with external organisations.

Individual barriers

As in wider society, DASVS carries a stigma. Many victims and survivors feel embarrassed and a personal sense of shame, often led to believe that the abuse is their fault, rather than the responsibility of the perpetrator. This prevents people from disclosing the abuse and seeking help. In a military community, these feelings are intensified further by a heightened fear of mistrust in the chain of command, the impact of the consequences and the perception of a culture where ‘a secret is never a secret.’

‘A caveat here, I don’t think there’s any research to back it up, but this is my opinion, lack of trust in the chain of command, stigma, fear of the consequences, if the perp is serving, at risk of losing their job, families may live in service accommodation. It’s a lot for a victim to take into account, what they stand to lose in leaving an abusive relationship.’

‘We’re not on operation now, but I think people would have thought if they said anything they wouldn’t be able to go on tour.’

‘Rank may be an issue in relationships. It’s a power issue, credibility. A more senior person might be believed, have an impact on a person’s career, whereas if the victim is a lower rank the perp may tell them they’ll never be believed. There are real complex problems that may not exist in other settings.’

‘Rank is an issue in a hierarchical system. If the higher rank is a victim/survivor, they may feel shame. We also have the commonwealth community where if they are a spouse, may be worried about deportation, having to leave their children behind. The LGBTQ+ community, if not common knowledge, the threat of being outed.’

‘For families from the Commonwealth countries there are a lot of cultural issues, male hierarchy is really embedded and there are lots of implications if they return to their home country, they can be disowned by their own families and lose their children.’

‘But for Commonwealth families the wives have no legal status and effectively become asylum seekers with no recourse to public funds.’

‘I think we have all the same barriers and challenges of Civvy Street, but we’ve got a few extra as well.’

The quotes above demonstrate the individual barriers that exist, in particular, the lack of trust in the chain of command, concerns about not being believed, the impact upon careers and cultural issues that may increase the risk to and vulnerability of the victim. An important issue raised by one participant is the role of drug misuse in relationships, or the facilitation of drugs in the perpetration of abuse. This has the ability to silence victims due to the policy of zero tolerance towards drug misuse within the military:

‘We have zero tolerance for drug misuse and we don’t have any discretion around that as a police force. It couldn’t be ignored and this could silence victims. They have every incentive not to use drugs, but they still do it and people can’t admit it’s a problem as there’s no support available.’

The serious consequences of these barriers is that they cause delays in disclosure and heighten a reluctance to seek support at an earlier stage. As a result, many cases are already at a crisis point when they come to the attention of Welfare Services or Commanding Officers. This has a significant impact on demand and the capacity of the AFA, as these cases are often more complex, requiring longer-term specialist intervention and additional resources. If intervention is initiated at an earlier stage, the AFA can work with the victim to assess the risks and provide information to enable them to make informed choices about the best way forward for them. This may involve working in partnership with the welfare services to improve safety planning and reduce risk whilst longer-term solutions can be found.

‘We talk about this [individual barriers] quite a lot, it’s brought up in training with Aurora. Their experience and what they‘ve heard from victims is very valuable to us, it provides a victim perspective. We talk about it to Commanding Officers when we talk about DASVS.’

This highlights the benefits of undertaking training with an outside specialist organisation, as their knowledge and experience helps to provide a victim perspective. This information is disseminated by participants to others within their own organisation and raises awareness of the barriers that can exist. Encouraging signs also emerged from the findings of other factors beyond the organisation starting to influence military culture, in particular, the people they recruit. One participant has started to see a change among recruits and is detecting a significant culture shift that is ‘being driven by the youngsters coming in now.’

‘We recruit from society, therefore, we reflect society and I think in society now people are a lot more open. In the schools and universities, as soon as you walk in help is available. Very few senior officers, the old and bold, will fess up if they’ve got an issue, but the youngsters, 16-32, will come and wax lyrical.’

This is important, as it illustrates how changes in wider society are able to influence organisational culture through the attitudes of younger recruits and their expectations informed by previous experiences. The increasing public and media focus on mental health, and the ascendance of domestic abuse and sexual violence on the political agenda, has increased public awareness and this knowledge is now permeating institutions through recruitment. How those attitudes and expectations are further nurtured or manipulated then depends upon the power of the organisations own culture, and how far people may have to compromise their own values and beliefs just to ‘fit in’.

Organisational barriers

An essential stage in achieving organisational change and influencing organisational culture is an acknowledgement of the problem in the first place. A number of the individual barriers identified above relate to the wider organisational culture, in particular, a lack of confidence in the chain of command and a mistrust of the processes that may follow. To build confidence and regain trust, actions need to be taken at the organisational level that send a clear message that organisational culture is changing and that the safety and well-being of military personnel and their families is paramount. Such organisational change can only be achieved through strong leadership and the development of policies and processes that are implemented at all levels, demonstrating sufficient progress is being made to change minds and professional practices.

A number of the participants have been involved in the area of DASVS in the military for some time, whilst for others it has been a relatively new challenge.

‘I’ve been involved in the DVA side for quite a while now. I Chaired a domestic abuse policy group when the centre were fairly disinterested. The centre was focused on adult welfare, specifically serving personnel, to keep them active and minimise disruption to the service. Domestic abuse has always been around, but prominence, profile, awareness and understanding has increased over the years and we very much mirror that. It is changing.’

‘In order to change the culture, the Army needs to see that DVA impacts on operational effectiveness, both if you’re a survivor or a perpetrator’.

The key issue here relates to the core business of the institution and for the Armed Forces it is the protection and security of the country. An effective military relies on the ability of its personnel to carry out their operational duties, so the emphasis is upon the training, fitness and retention of its serving personnel. As a consequence, only factors that affect operational effectiveness will be deemed a priority. Therefore, if DASVS is not considered to impact adversely upon operational effectiveness, then it will not warrant sufficient resources to raise awareness, provide support and develop strategies to prevent it. For an analysis of how the divisions between the public and private spheres are further framed through the needs of operational effectiveness, see Gray (2015).

The MOD (2020a) acknowledges that the sacrifices often required to achieve this constant state of operational effectiveness can have an adverse impact on military personnel and their families. In an updated leaflet outlining the progress of the first Defence Domestic Abuse Strategy – 2018-2023, it reiterated its commitment:

‘…. to coordinate efforts aimed at reducing the rate and impact of domestic abuse and increase the safety and wellbeing of those affected. We will develop a culture of support and play our part to support the criminal justice system where appropriate…. We will work across organisational and departmental boundaries to ensure the quality and accessibility of services that are readily available so that anyone experiencing domestic abuse has prompt access to help and support regardless of their location or position as serving person, family member of civilian employee. We will do more to breakdown the invisible wall that deters victims from asking for help. We must have systems in place that allow us to respond and support as soon as it is needed and to the maximum effect.’

(MOD, 2020b: 4)

A participant acknowledged the efforts the MOD are making in order to catch up with the pace of change happening in wider society, including initiatives involving outside agencies:

‘The MOD like to see itself as a good employer, they may be a bit slow to react, but when they see an issue is emerging, then they will embrace it. We’re just going through this journey… from a fairly low standing start, building up our polices and the important thing that has gone alongside this is the engagement with the third sector. All forces are now a member of Employers Initiative Against Domestic Abuse (eida.org.uk).’

To improve responses to crime, the Royal Naval Police (RNP) identify certain types of offences as a priority and assign a designated commissioned officer to act as the Plan Owner. The Plan Owner is tasked with reviewing strategy, training and education. Participants agreed that leadership was important in this area and made the following observations:

‘Some people are reluctant to delve into domestic abuse, either because they have lived experience, or they don’t get it and they don’t want to get it. It is a very difficult area to work in. If you’re going to do it well, you really need to care.’

‘RNP is a very insular, autonomous institution, and has the ability to do most things internally, but this particular plan…it has really opened up our peripherals and we now work closely with civilian organisations, it cannot be something that is managed in a singular form.’

As seen above, choosing the right people to take on key leadership roles can be challenging and this was an important subtheme emerging from the data. To have a significant impact and drive change forward it is fundamental to have the right people in the right positions:

‘Cultural change is personality driven, it depends on the people round the table. There is momentum at the moment , lucky to have the right people owning the policy, like the work we’re doing on the JSP 913 at the moment. But in the forces people routinely move on and you have to keep re-educating time after time. It’s hard work and very frustrating.’

The frequent change in personnel was a point raised by participants and highlights the negative impact of losing ‘organisational memory’, requiring those present to ‘repeatedly educate’ those new to the table. This loss in momentum can lead to delays and increasing frustration at the lack of progress:

‘In my humble opinion, the group has good intentions, such passion, but there is too much talking and not enough action… we feel frustration by the lack of progression, we’re doers and fixers, there’s only so much talking… I acknowledge there has to be fine detail in policy making, but sometimes you just have to push things forward and get on with it.’

‘It’s a big group and responsible for delivering the five year strategy, but already 12- 18 months behind. The revised JSP 913 was meant to be rolled out by the end of the year. They weren’t overly ambitious, there just isn’t much holding to account.’

The above quotes demonstrate the challenges in developing and reviewing policies, in particular, the involvement of people from a range of departments and the need for clear accountability to keep on track and ensure tasks are achieved by the deadlines set. This is a frustration common to many large institutions when attempting to effect cultural change, but is an important part of the process and requires strong leadership from the top.

The third pillar of the Strategy (MOD, 2020b) is Partnering and this demonstrates a willingness to engage with outside organisations. The next superordinate theme examines how the development of partnerships between military and civilian organisations assists in raising awareness of DASVS, promoting joint-working and improving collaboration.

Raising awareness of DASVS – training and resources

Partnerships

In Hampshire, a local domestic abuse forum set up a local military subgroup. Key to the establishment of this group were concerns very similar to those of Aurora outlined above; although the region had a very large military population (15-20%), very few referrals were being made to local support services from military families. The role of the subgroup was to investigate this further by bringing together key stakeholders from the local civilian and military communities:

‘The Garrison Commander was quite nervous initially due to wider criticisms. At the time, there was negative media coverage of PTSD, criticism of the Armed Forces and how it was letting military personnel down. There was a hesitancy as to how it [DVA in the military] may be portrayed in the media.’

‘It takes so long to build up trust, the Armed Forces are quite nervous of people coming from external agencies and kind of medalling, if you know what I mean? But there was a community beat officer (military police) at the time who was very supportive and had a range of contacts…. they were the lynchpin and helped us to work together.’

The subgroup secured funding for a pilot research project to be undertaken by Williamson (2009) with the aim of gaining a clearer understanding of DVA in a military context, to examine the services available to military families and to identify what further interventions may be required. As observed above, a common frustration with any multi-agency collaboration is the turnover of people involved, but key to the membership of such groups are the local providers of specialist services who can share both their local and specialist knowledge, helping to provide a wider victim perspective.

‘There’s quite a lot of churn, you get someone keen, then the personnel change, lose momentum. They come up with the same ideas. But little progress is made. There needs to be more consistency. Aurora joined the subgroup when it received libor funding and it helps to keep the wider context.’

An outcome of the military subgroup’s work was commended by a participant: ‘One of the funding streams we were pleased with was the development of an online toolkit which is on the MOD website.’ The purpose of this funding was to help raise awareness of DVA and the support services available by developing information pages for the MOD website, specifically tailored for military personnel and families.

Work was also undertaken on developing a protocol for joint working between the military and civilian police, with the hope it could be rolled out across the 43 civilian forces, but this was halted to wait for the Jurisdiction Guidance to be updated, but this has still to be agreed.

The AFA Project assisted in developing stronger links and partnerships between external agencies and internal departments, in particular, through the delivery of specialist training.

DASVS Training

A significant benefit of joint-working is the provision of training by specialist outside organisations to military personnel. This provides an opportunity for the specialist service to share their knowledge of DASVS and for them to gain a greater understanding of the military context and the role of welfare services in the provision of support and practical services. A gap identified in the MOD strategy was the provision of relevant training, subsequently filled by Aurora.

‘There is nothing in the MOD strategy about what training is needed by professionals operating at different levels and in different roles when working with victims, so it’s a piece of work we’re doing at the moment. Stalking is very high on my radar at the minute and we would have liked them [Aurora] training us, their experience and them being our consultant. They were going to do a train the trainers event, so that whole knowledge about stalking could be rolled out, but unfortunately the training didn’t happen as it was just as COVID hit. I know they’ve started this up again and running virtual training, but I couldn’t go and I’d really like the train the trainer programme.’

There was agreement that the provision of training was a wider institutional issue and that competing needs for training put additional pressure on the resources available: ‘The MOD is a big complex organisation. If you want to generate cultural change, it’s a complex thing to do. Someone will come up with an idea and write a policy, but need a route to provide training and there is so much pressure on training capacity. Everyone wants to get into the training because everyone’s subject is important.’ In order to achieve cultural change and raise awareness of DASVS, one participant suggested that DASVS training needs to be incorporated earlier, as part of basic training:

‘The DASVS training should be rolled out from the time of recruitment, at least a basic level of awareness of DASVS, what’s acceptable, and then more training throughout their career as they progress, more information on how to recognise it and approach it with the people they are responsible for. It takes time and there needs to be a firm mandate for it, we haven’t quite got it at the moment.’

This would assist military personnel transitioning to a commissioned officer role. One participant felt that the training provided at the time they took on the role of a Welfare Officer did not sufficiently prepare them for what was to come:

‘After years in the Army I became a commissioned officer, a role as a Welfare Officer. It was just one of the roles available, I’d had no previous contact, knowledge or experience of welfare work. We had one week of training in York by an outside company that wasn’t fit for purpose, you go away for 6 months and then a 4 day top up. We’re not taught to do anything. We listen to a person’s story then flag it to welfare, but it could take six weeks. What do we do in the middle? We’re dealing with murder, rape sexual abuse and a range of serious issues, nothing can prepare you for that. It needs professional people like Aurora…. Ground truth.’

This participant later attended training by Aurora, which they found more engaging and assisted in furthering their understanding of DASVS:

‘The training by Aurora was worlds apart. They took the audience into account and it was more interactive, much better than sitting and watching a video. I’m a big fan of Aurora, I’m not going to lie, I got a lot more out of it, but that’s may be because I trust them… and they’re not afraid to challenge you.’

Another important aspect of the training identified by a participant was the ability to understand the victim perspective, how to respond to a victim/survivor, especially during the initial contact and early stages:

‘The AFA did some training on about talking to the victim. It’s all about the wording. Instead of just giving them a leaflet, which could be just another obstacle, another person they have to engage with, tell them about Aurora and ask if they’d be content if you make a referral for them, take that problem away from them. So I thought I’d give this a go with a sexual offence, a rape, and low and behold, within 12 hours they were connected and she had a case opened with Aurora.’

‘One thing the AFA has taught me, is that you can’t accuse people of being a victim. Which is very easy for us, we’d just say it as it is, we’d literally just tell someone they’re a victim, but the AFA was horrified. So by playing through some scenarios, we can see things more clearly. So I’ve learnt a lot, I didn’t know there was such a thing as financial abuse, but had a case recently, looked into the referral, potential financial abuse.’

The victim in one case was a man and this helped to raise awareness that men can also be victims of DASVS. Men’s experiences of victimisation are often marginalised and they can face additional barriers to disclosing abuse and seeking help (Davies, 2007: 189). In particular, men fear being thought of as weak or vulnerable, concepts not often associated with masculinity, power and strength; characteristics most highly valued in the military.

‘There’s a man here whose wife is controlling, nasty, keeps ringing the police on him. We check on him every week, he’s on the register, but unfortunately that’s all we can do. We don’t call them charities, we just advise of their name and give information on what they can do, but he hasn’t engaged yet.’

Whilst not yet engaging with support services, the man will remain on the VRM (Vulnerable Risk Management) register and contacted regularly. On these occasions, further opportunities are taken to encourage people to engage with support, offering them a choice of services available in the community, including those provided specifically for men. Raising awareness of both internal and external services is central to enabling people to make informed choices and various awareness campaigns are undertaken to achieve this.

Awareness campaigns

An important function of training is raising awareness of the types of support available in the wider community that military personnel can access. In addition to and alongside the training, awareness campaigns are held on military bases to achieve a greater reach. In November and December in 2019 events were held with the Army and RAF as part of the 16 Days of Action initiative, involving lectures on Coercive and Controlling Behaviour and the role of the Armed Forces Advocate. Presentations by Aurora have been delivered to Senior Naval Officers on DASVS, lectures provided on a range of DASVS matters as part of Army Study Days, and a session on DASH Risk Assessment for Royal Navy Police. Use is also made of visual aids (posters) and social media:

‘It’s a big buzz word at the minute, I do get that and I think it needs to be. We run campaigns and put up posters, it’ll go on Regimental Orders. We have a Facebook page, it goes out to families as well. It raises awareness about being a victim and provides numbers that people can ring.’

‘We do have all sorts of briefing channels that you can propagate information through, social media, so there are various communication methods, but at the end of the day… until you recognise you’ve got a problem then this kind of stuff just flies over your head.’

‘We are starting to get more referrals for DASVS now, people are prepared to come forward and do come forward. I was recently talking to a leader from the Figian community, she is married to a soldier and she has kind of taken on the role of leading things, and was saying how positive the people in her community have been about the support they have got from the AFA.’

This indicates that a combination of training and raising awareness through military communities helps to improve peoples’ understanding of DASVS and the support available, although further work is required to ensure that it reaches everyone. The next section examines the role of the multi specialist AFA. Evidence from this evaluation highlights their dual role as an independent advocate to victims and survivors, and collaborative partner to military police and welfare officers. In particular, the study found that the AFA acts as a go- between, a crucial link between the two.

The dual role of the multi specialist AFA

When listening to participants talk about the AFA, their role and their contribution to supporting victims and survivors, four significant factors emerged:

- their independence from the Armed Forces;

- their ability to gain the trust and confidence of those they worked with;

- their ability to provide a crucial link between the victim/survivor, the welfare services and the criminal justice system;

- their ability to improve the outcome for victims/survivors, to help regain a sense of autonomy through informed choices.

Independent

As outlined above, in addition to the barriers many people face when experiencing DASVS, military personnel may face barriers that are unique to the organisation and communities they live in. This means that a crucial part of the role of an AFA is their independence from the military, to sit outside, but remain just close enough:

‘There are barriers to people reporting so her independence is very important. People often fear we’re too close to the chain of command, and although we are absolutely independent of the chain of command, we do work in the system, so we’re not perceived as such. I think the AFA gives us additional strength in planning and in training, and in knowledge sharing.’

‘I think because they are not military, although the AFA is in her own unique way, I think that barrier is reduced, there’s no perceived judgement, or this person is going to run and tell my chain of command, or it is going to end up in my annual report, all these different things.’

‘It’s important to have that external provider, one that actually has an understanding of the environment people are in. Because even though a lot of our families are living in their own homes, the experience of being a naval partner is very different to many others, especially those in their local community, and to try and explain that to somebody while you’re also trying to tell them about what you’re going through, it’s just another dimension that people could do without really, it removes that other barrier.’

This demonstrates the importance to victims and survivors of having someone they can go to who is independent from the military, but who has sufficient knowledge to understand their environment and the potential consequences for them of disclosing and seeking help.

‘Victims want an independent service, but one that understands the forces. They [the AFA] get an unusually high number of self-referrals. Word of mouth. The AFA is willing to challenge and has got a reputation!’

‘Independence is key. Someone totally independent, outside the chain of command, not part of the military. The AFA is very forthright, willing to challenge, but within the boundaries. You can only do that when you’re an independent organisation.’

‘I was contacted by the AFA one evening and she was raising concerns about how the chain of command was dealing with serving personnel who are victims, and basically rather than moving the perpetrator they were moving the serving survivor from their own house. Rather than contacting the civilian police, they were taking the easier option and getting the CO to remove the only person they could remove, the serving survivor. By challenging the chain of command, the AFA alerted us to very lazy thinking and not considering the impact of the survivor. They were having to pay twice for accommodation, and all sorts of levels of additional abuse as a result really. We’ve now made our staff aware of the action that can be taken if this comes up again.’

As highlighted above, a key strength of the AFA’s independence and knowledge of the system is their ability to challenge. Having an independent oversight can help to identify areas of practice that require improvement and provide opportunities to share best practice.

‘Her [the AFA] knowledge is really good. She knows her way round systems and she knows the short cuts, but at the same time she is very respectful of them. They are very different cultures, you can’t just bulldoze your way through. The AFA had a head start because she has lived it, but that’s not to say someone who doesn’t have that military background couldn’t learn it.’

‘Their independence is important and why for me, Aurora are always the referral of choice. Also because they are not process-driven. To make a referral to the Welfare Service there are so many hurdles, we have to explain to the victim what they need to do… Officers may not have the confidence, so they can call the AFA and make a referral, it’s a simple process, much easier for people.’

‘I think they are invaluable to what we do and the service they provide to victims in the Armed Forces. It think it’s very important that we have an independent body, because lots of people don’t trust the chain of command. Independence is really important, but because they are an Armed Forces Advocate they understand the issues and I think we’ve assisted them on that journey as well…. We’ve assisted them to understand Armed Forces policy which I think helps them to give better advice. That relationship has really developed and flourished over time.’

The views of participants above demonstrate the importance of partnerships being a two- way process, sharing knowledge, improving processes and developing effective partnerships built upon mutual trust and confidence.

Trust and confidence

‘When I first got into Welfare I had literally no idea about the AFA. I didn’t know it was there. I had a young girl kept reporting domestic abuse, her partner was a serving soldier and she had a young child. I referred it to Welfare and Social Services, but it would all take a couple of weeks. I spoke to a Welfare Officer and they said “why don’t you just give Aurora a ring”. Luckily for me, the AFA was in the area and we met an hour later. So it was kind of by accident.’

‘What Aurora do is provide someone who is invested and very, very quickly I built up trust with the AFA. Any advice they gave was absolutely on the money. Especially for someone who was as inexperienced as I was… it gives you confidence in what you’re doing.’

‘I’m pretty fortunate because I more or less have [the AFA] on speed dial. Welfare are a small team with a huge workload, so having someone who deals with this and professionally qualified in this area is great. She knows and understands the military culture and processes, you don’t need to explain them.’

‘She [the AFA] is straight talking and as soldiers that’s what we need, we don’t need flannel. The thing is, she’s honest. She doesn’t put ideas in your head, she’s very engaging and asks “What do you think is happening, what is the outcome, the answer?” She helps you to see the wider picture.’

‘The AFA has built up so much trust with the regiment that if she says it, it’s done, let’s do it, there’s no questions. It’s purely because the advice she’s given has been right.’

‘The value of the partnership is (a) it feels safer, because there’s more than one brain looking at the problem, there’s a huge strength in collaborative working, none of us have a monopoly on good ideas. And (b) her focus on the survivor and her real in-depth knowledge, she is so engaged with the person enduring the DVA that she’s able to get an insight to the perpetrator’s pattern of behaviour… helps decision making for the chain of command.’

As will be seen in more detail below, it is crucial to build trust and confidence with victims and survivors to ensure they remain engaged. A valuable lesson learnt by a Welfare Officer following the advice of the AFA.

‘It’s easier to deal with DVA if the victim is the serving soldier, as you can do a lot of stuff with them in work time. When it’s the civilian partner, we have to be a bit clever. As explained by the AFA, we can’t just march round to the house, someone may be watching, so she advised to “get her to ring you when she’s free”. It was a self-referral and it was important to build trust…. Confidentiality is key, you have to do everything they’ve asked you. If they’ve said “don’t ring me for a week” the temptation is to ring them, but you don’t. Once you’ve gained their trust, they will talk to others, word of mouth, “the welfare officer is gleaming, go and talk to her”… word gets out when you build that trust.’

This example demonstrates that once you have won the trust of survivors they are more likely to remain engaged with support services. They may also be more likely to share their experiences with others, which is central for raising awareness in groups that may be hard to reach.

Collaboration

This study has found examples of how the AFA acts as a crucial link between the survivor and the internal welfare services. Once confidence and trust has been established between the AFA and the survivor, the AFA is able to link them back into the welfare services with someone the AFA knows and trusts. This is often in relation to cases where practical support or action is required.

‘The AFA does the emotional support, provides information and advice, and the Armed Forces contacts help with the more practical issues. Working closely together we can ensure the safety of the victim.’

‘Aurora… they think ahead. Very tenacious, if they come up against a barrier they will try and find another way, backed up by the rest of the team and all their knowledge.’

‘We wouldn’t have had the good outcomes in half our cases. I could have done more damage to my service personnel if I hadn’t met [the AFA]. We’d just bulldoze in….’

In particular, there was significant evidence of the AFA acting as a link between the Armed Forces and the civilian police and the wider criminal justice process.

‘The AFA is seen as a professional, being part of that environment, people actually respond to her and the police engage with her, rather than me. If I rang up the police, they’d just fob me off, yeah, we’ll get back to you, whereas when the AFA phones, she knows the system and I think they’re quite afraid of her.’

‘I don’t think we’d be where we are now without Aurora…particularly the AFA, it has just shown the value in the multi-agency approach with this offence type and by opening these doors, the services it can afford victims/survivors of this offence type.’

‘Our working relationship with the Home Office police is so much better, we’ve advanced, but still got some way to go before the Home Office police see us as a recognised policing agency. DVA has always been there historically. When Hampshire police attend a DVA incident it may not have historically been passed on to us. Whereas now there is a formal way of reporting, we get the sweep up and have got a better working relationship with them. They are being captured a lot more now as well.’

‘We’ve built back up the relationships with Hampshire police now, intelligence sharing, just by attending the Stalking Clinic. Sitting round the table, people starting to see us again as a professional body and actually, because we do not have the same volume of crime, we have more time to be a little more thorough, they see the standard of the product we’re giving, which is a good thing.’

‘We have started doing secondments, they have a RNP officer working in Amberstone [a specialist sexual offences investigation team], a new initiative, so they can see what we bring to the table.’

‘There are benefits of service police sitting on MARACS [multi-agency risk assessment conferences] involving service families, because of the complexities. Things we can ask about support for victims and perpetrators, which we wouldn’t be aware of if not sitting around the table.’

These examples demonstrate how links developed between the AFA and military personnel have resulted in creating closer partnerships with outside agencies and improving best practice and outcomes for victims.

Informed choice

An important subtheme to emerge was the importance of giving people a choice. This has been widely evidenced in other studies focusing on what victims want (Wedlock and Tapley, 2016). At the initial point of disclosure, individuals may prefer to work with an independent organisation, for the reasons given above:

‘…but what is important is the partnership working between the AFA and the RNFPS, and COVID has proved that. Once the AFA became overwhelmed by the demand, they worked in partnership and services were maintained, so that’s the key really, giving people choice, especially in the initial stages, and then once they’ve engaged they might be reassured that they can go to the other organisation without the negative repercussions which they think might have happened.’

People working in the Welfare Services are aware of the stigma still associated with contacting their services and that this is mentioned in the ‘Walking in their Shoes’ report (MOD, 2020a), where there is a model aimed at de-stigmatising help seeking through developing hubs in the community.‘Everybody needs help in life at some point and there is something stigmatising about the culture, but I don’t think it’s all about the Army Welfare Service. I think it’s more about people who are enduring DVA needing to have a choice of where to go, which is the benefit of having somebody like Aurora, because they are separate, but alongside.’

‘Aurora are very pro-active and have developed a very good profile. They focus on building links with people. They identify the right people and are then able to develop those personal links and build confidence.’

A greater awareness of the partnerships available assists welfare officers, together with the AFA, to provide victims and survivors with information that enables them to make informed choices regarding what is best for them. This includes an awareness of other outside support agencies; multi-agency partnerships that exist through the operation of MARAC’s, MASH’s (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hubs); the Hampshire and IOW Stalking Clinic; and the Amberstone team (a specialist police team focussing on investigating sexual violence).

The value and impact of partnership working

When reflecting upon the value of working in partnerships, the overwhelming response from participants has been the positive impact of working with the AFA and Aurora, in particular, in helping them to perform their own role and the value of this to their organisations.

‘I enjoy working with Aurora, they’re very open, they’re very interested in getting things done, it’s good partnership working, certainly for me at my level and as I understand it, from the practitioners as well.’

‘It’s very important having a sounding block where you can discuss and bounce ideas off each other, but I think the RAF have had very limited engagement, and if you’re talking about mainstream funding, it’s got to have a wider reach. I think they [Aurora] are now well established and hope there will be a way found for it to continue.’

‘Their response is very quick, she’ll ring you back within a day or two. If the AFA is not available, then another member of the team will pick it up. They’ll always get back to you.’

‘What I find is you often have a big service come in and get the contract as a commissioned service and they’ll only deliver what they’re paid to do. Aurora have managed to sit outside of all that, they’re more innovative and able to spot the gaps. A bit more kind of, we’ve got these specialist projects, but we need to be paid properly for it. They’re not in a race to the bottom, to be the cheapest, but these smaller, independent grass-roots services, give them £5,000 and they’ll make £50,000 worth of difference.’

‘The Aurora team are always amazing, they always come straight back if you email them, which is so important. So many places you can’t get a response. If people reach out you need to pick up on it almost straight away, or it just drops off their radar again. For developing partnerships it is very important.’

‘That then shows when you’ve got a service that is really quite sensitive, like the Armed Forces, where you need to build that trust. People need to have confidence in the service and whenever they contact Aurora they know they will get a good response from them.’

‘A couple of times I’ve got it wrong. The AFA has picked up the referral and got back to me and said “it’s not that, it’s this.” So it’s been closed down, but she’s given me another avenue to go down. She’s always honest, she doesn’t fluff me up, if I get it wrong, “you got it wrong”’.